Gadir: Phoenician Cádiz through its artworks

A guest article by Mercedes de Santiago | February 2025

About Mercedes de Santiago, this week’s guest writer

Mercedes is a lawyer who writes about art and history on her Substack newsletter,

. She also shares her serialised fiction story, "The Legend of Sinardia", exclusively on Substack. Make sure to check out more of her posts at the link below!If you’re new here, the Society of History Writers is founded upon the principle of collaboration. It’s the ONLY space on Substack dedicated to bringing writers of history and historical fiction together to share their experience, grow in their craft, and share their writing exclusively with a growing worldwide audience. I am honoured to provide this space to spotlight your writing and share it with colleagues and readers across the world.

Gadir: Phoenician Cádiz through its artworks

Mercedes de Santiago

1. Introduction

One of the most special peoples of Antiquity were the Phoenicians. Unlike the military empires of other contemporary people, they forged a primarily commercial one, in which the colonies were important centres where goods, ideas and influences were exchanged between the settlers and the natives. These commercial colonies extended throughout the Mediterranean, reaching the westernmost side of it. Thus, among other cities, it was they who founded Gadir on some islands in the south of what is now Spain. This article aims at a brief study of the pieces of art found in this area of influence and what they tell us about this remote past.

1.2. History and Geography

First we must make a brief historical and geographical introduction to the time and place we are referring to.

1.2.1. Historic coordinates

We will use them afterwards to study the artworks.

a) from Gades’ foundation to the fall of Tyre under Assyrian and then Helenistic rule: it’s believed that the city’s foundation took place in 1104 aC,1 what would make the city the more ancient in Western Europe. Early archaeological discoveries have long suggested that the city was founded in the 8th century BC. However, more recent archaeological remains have in fact been pushed back this proved date to the 9th century BC.

b) from the fall of Tyre and the rest of the Phoenician cities in Eastern Mediterranean: the conquest of the Eastern Phoenician cities made people who didn’t want to fall under foreign rule, to flee for their Western colonies, Carthage, Southern Italy and also Southern Spain. That resulted in a rich exchange of influences, among other Hellenistic and Egyptian ones.

1.2.2. Geographical coordinates

When we see the map of Cádiz nowadays, it seems its area was always united. But if we look closely, we can see the remains of the old Channel that separated the two main islands. We can even now see on the left of the image the submerged canal, which continues under the city.

The Channel between these two islands, named Eritheia and Koutinoussa, was used to build its harbour. That provided a great place for the ships (and their cargo) to be protected both from enemies and the Strait’s winds. Gadir, in their own language, meant “fortified or closed enclosure”, because of the walls that protected the city.

In fact, that harbour’s dock from the 3rd century a.C. can actually be visited as it was discovered under the city of Cádiz in the 20th century. Dug into the natural rock itself, it has served to better understand how the city was laid out in those early times, and is a reminiscent of the fight between Rome and Carthage in Spanish territory. In fact, part of the remains are, in fact, the dry dock where Punic builders made their own warships to fight the Roman Republic in the area.

But the area also includes another island, that was called Antípolis (nowadays, the Island of León), in which remains of the past Phoenician splendour have also been found. We can also locate in the map the three more important temples the city had in those times: Melkart’s to the south (Koutinoussa), Baal’s to the north (Kotinoussa) and Astarté’s in the north (Erytheia). All those temples’ remains have actually made it easier to tell the story of the city in those Ancient times.

2. After this brief introduction, we begin the exam of some of the artworks found:

Beginning with the first period, we will examine one of the most interesting pieces: this thymiaterion or perfume burner was found in the neighbouring city of Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Its origin was the Algaida sanctuary, dedicated to a female divinity, probably Phoenician goddess Astarté.

Its importance is striking because its a unique piece, not found anywhere in Western area. Made of terracotta with three equal sides in which moons are represented, it’s a great example of the mastership in the area in the 7th-6th century BC. Astarté, goddess of fertility, was symbolised by the planet Venus and the moon, associating her with astronomical navigation, hence its importance in Gadir.

The temple was afterwards dedicated to the Roman goddess Venus, mentioned in his works by Plinius the Elder.

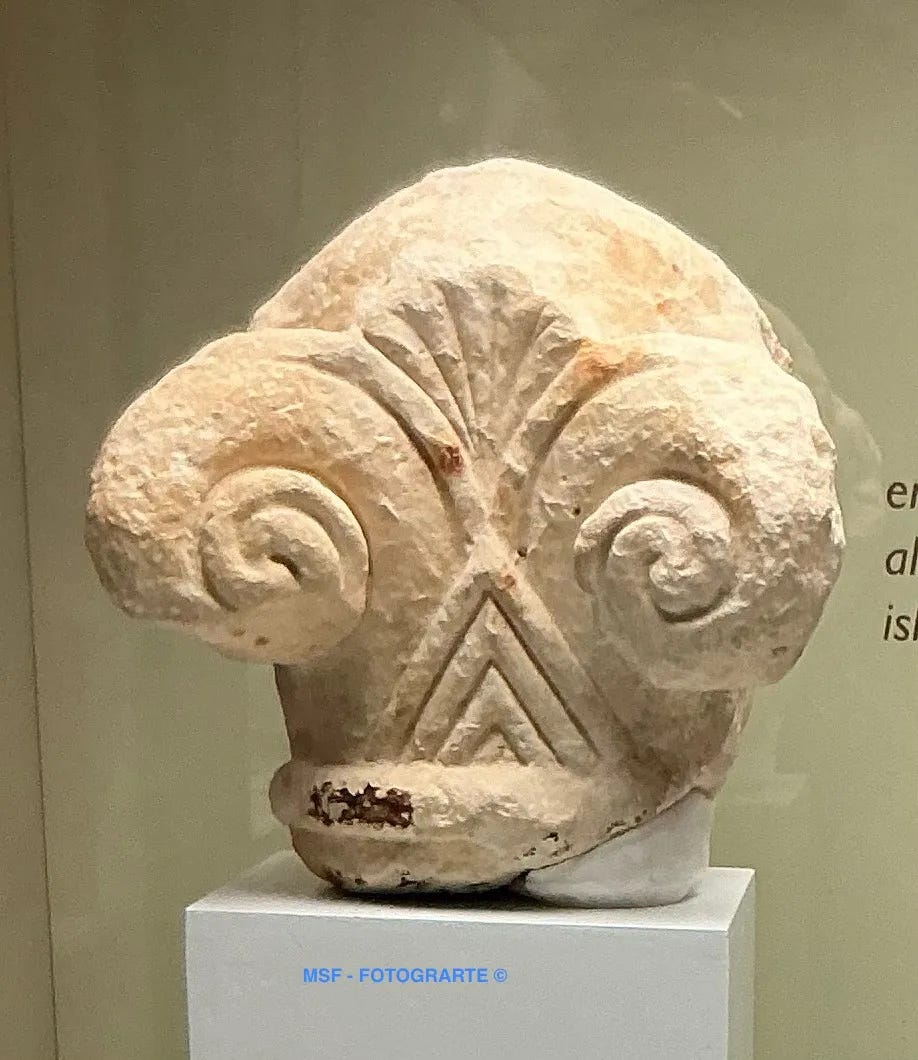

The second one is this surprising chapiter dated from the 7th century BC. Due to its oblong top, probably had only an ornamental, not a constructive, function.

This type of chapiter, also called "proto-Ionic" or "proto-Aeolian", was quite common in Syria-Palestine in the constructions sponsored by the various royal houses, as we see in places such as the first temple of Jerusalem, Samaria and Megiddo. In these Eastern temples, they were found flanking their main doors. It probably indicates the location of the Baal temple in the area.

Being Melqart the greatest of the Phoenician gods, some of his images had been found in the area, pointing to his temple in the south area of Kotinoussa. These ones, with Egyptian influence, were found in the area now known as Sancti Petri.

The literary sources of antiquity describe the temple and the rituals that were practiced there. The cult was entirely Phoenician, very similar to that carried out in Tyre. In Roman times, it was striking for being something very different from the usual religious ceremony of the classical world. At an archaeological level, we know very little about the temple of Melqart. The dating of the pieces must be placed in the 7th century BC.

This Warrior, made locally of oyster stone, was among the materials that constituted the filling of a well and had been moved there from another place for unknown reasons. The attitude of the figure, as well as the knee-length skirt, the cap and the pointed beard, respond to an oriental iconography in which a warrior, with his body bent, thrusts a spear into a fallen animal or a wounded enemy on the ground. Its chronology is placed around the 6th century BC, approximately.

After the Tyre’s fall and the flight of a part of his inhabitants to the Western colonies, the Hellenistic influence becomes the most relevant. Also, The Phoenicians were slowly replaced by the Punics, although for a time they would still be referred to as "Phoenician-Punic".

This tilting ring dates around the 5th-4th centuries BC. It was part of the grave goods of one of the Phoenician-Punic tombs discovered. Made with gold leaf and silver interior, the tilting element is composed of a rock crystal scaraboid on the flat part of which you can see an engraving depicting Pegasus with Bellerophon, a character who, according to mythology, managed to tame the horse. As we can see, the mythological image is now Greek, not Phoenician.

During the 20th-century, some huge discoveries were made, specially about sculptures, whether they were manufactured in the area or were imported. Both the mentioned Warrior and the following one are of great interest given the scarce presence of Phoenician stone sculpture in the Iberian Peninsula. Both are made of local sedimentary stone (oyster stone), with a stuccoed surface, and reveal the existence of monumental plastic art among the western Phoenicians, which is still little known.

This one represents a seated woman, now partially mutilated. The statue was later used as a stone block for a Roman tomb in the 2nd century BC.

We arrive to the best of the lot: the male and female Phoenician sarcophaguses:

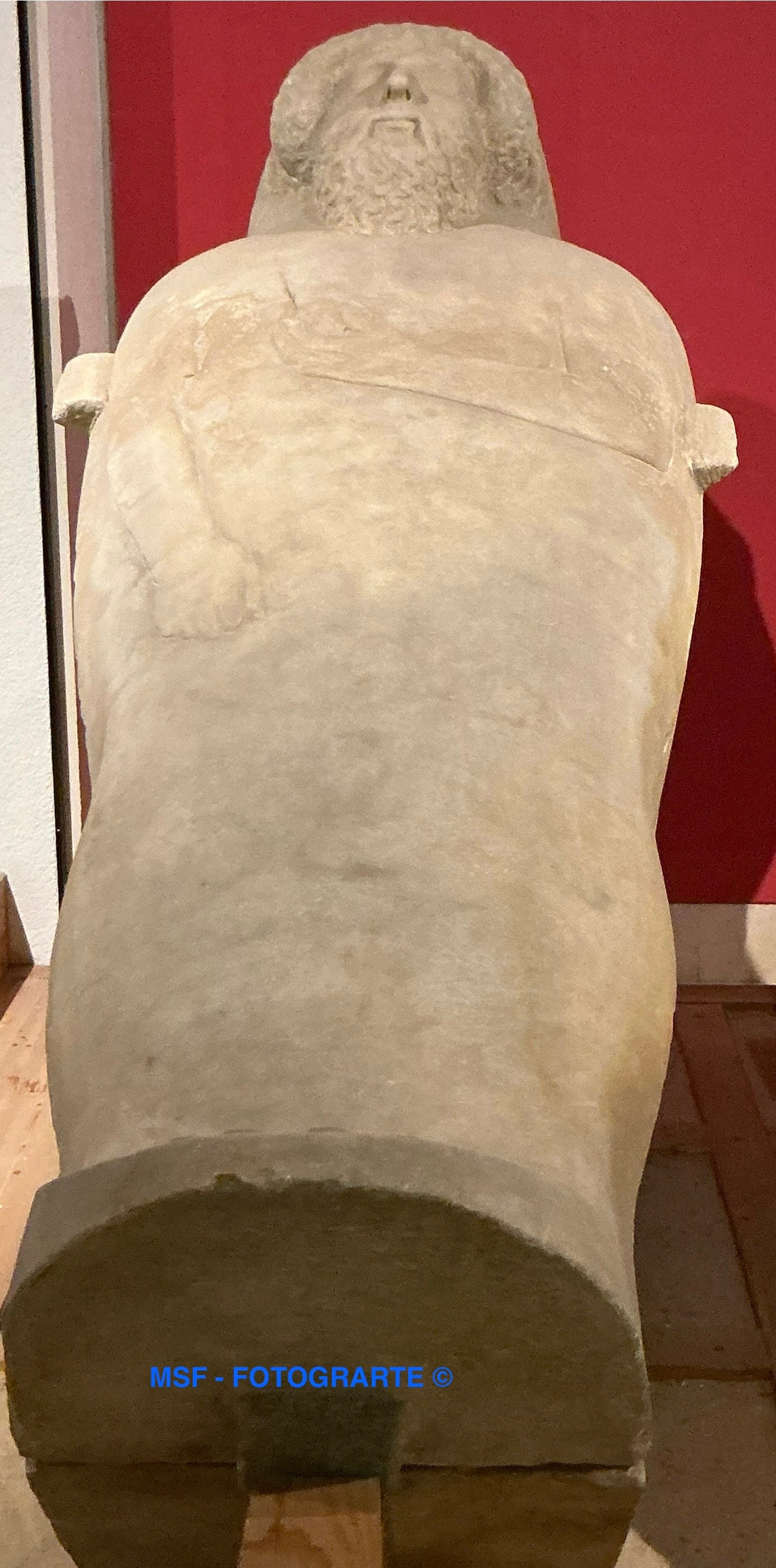

Dated around 400 BC, it represents a mature male character, with well-groomed hair and beard, holding a pomegranate in his left hand and a painted crown of flowers in his right, which is very lost. It is also the only sarcophagus of this type, with beard and arms, found in the world.

The female sarcophagus was made around 470 BC and was found by chance when laying the foundations for a new building on the site where Pelayo Quintero Atauri, a former Director of the Cadiz Museum once lived, who always maintained that, if there was a male sarcophagus, there had to be a female one.

Its origins are unknown: some scholars have defended that it was made in Sidón, now Lebanon and transported to Spain, being an example of the good relations between Eastern and Western parts of the Mediterranean Sea under Phoenician influence. Others have defended that it was made in Southern Italy or even in a local workshop in Cádiz, as a proof of its importance. Today, looks like the Sidonian origin is the correct one.

Thank you Mercedes for sharing these invaluable material finds with us!

Have you come across them before? How do they confirm or challenge your understanding of the ancient world? Join us in the comments to continue the conversation.

Want to write for the Society of History Writers?

All the details you need to know can be found in the post below. I look forward to hearing from you soon.

If you enjoyed this, here are three recent guest articles featured on the Society of History Writers.

Members!

Don’t forget that the window for feedback on your writing is open only until 25th February 2025. All details in the post below.