"Welcome to America": A generational migration story

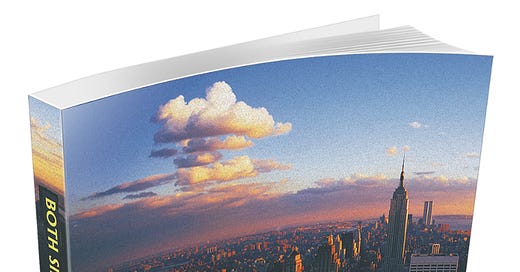

Excerpt from 'Two Sides of the Same Coin' by Michael Weiner

‘Weiner threads the ideals of philanthropy throughout the novel, as, over the generations, the four families channel their wealth into charities, medical work, and more. Just as altruism becomes a character in and of itself here, so, too, does New York City, as it grows and evolves alongside the novel’s cast, swelling and ebbing with the ups and downs that accompany carving out a life from virtually nothing. This is a poignant reminder that the true measure of success lies not in wealth or fame, but in the bonds we forge and the legacies we leave behind.’

(Publisher’s Weekly Review)

Pursuing the American Dream

I am delighted to welcome Dr Michael Weiner as the author of this week’s guest post, an extract from his novel Both Sides of the Same Coin. A native New Yorker, Dr Weiner is a paediatric oncologist, philanthropist, and author. He served as the head of paediatric oncology at Columbia University Irving Center and has written more than fifty peer-reviewed medieval articles and abstracts. He is the founder of the Hope and Heroes Cancer Fund, and has authored three non-medical books.

Both Sides of the Same Coin tells the story of four families and their journeys to New York in the first decades of the twentieth century. Over time, ‘they build success and give back to the community. However, with accomplishments come unavoidable heartbreak and misfortune, illness, drug addiction, and death.’1

This is the first of two chapters Michael will be sharing with the Society of History Writers; look out for instalment two which will land in your inboxes on Tuesday 25th March 2025.

If you’re new here, the Society of History Writers is founded upon the principle of collaboration. It’s the ONLY space on Substack dedicated to bringing writers of history and historical fiction together to share their experience, grow in their craft, and share their writing exclusively with a growing worldwide audience. I am honoured to provide this space to spotlight your writing and share it with colleagues and readers across the world.

Chapter 1: America

Michael Weiner

During the first decade of the twentieth century, America experienced a surge in European immigration. Immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Greece, Russia, and Poland arrived at Ellis Island with the hope of finding religious freedom, economic opportunity, and an escape from famine, tyranny, and political persecution. Each day, government inspectors herded and screened thousands of people of all ages and walks of life day through the processing centre on Ellis Island. Immigrants with a criminal record or with signs of disease or debilitating handicaps were denied admission and sent home.

The Italians and non-Jewish Eastern Europeans who were able to gain entry gravitated to the coal mines and steel mills of Western Pennsylvania and Appalachia. Greeks tended to favour the textile mills of the Southern states, whereas the Russian and Polish Jews worked in New York City’s burgeoning Garment District and as merchants in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago.

The immigrants who arrived without family settled in the ethnic neighbourhoods populated by their fellow countrymen. Here they could converse in their native tongue, practice their religion, and take part in cultural celebrations that helped ease the loneliness of being so far from familiarity. Life was not easy. Work was hazardous, wages low, and housing overcrowded and unsanitary, but in spite of the difficulties, few gave up and returned home.

Twelve-year-old Louis Rothoweskevitz journeyed from Russia to America alone. He had lived on the outskirts of Moscow with his father, mother, and younger sister, but life for Jews was marked by hardship and challenging circumstances characterised by political turmoil, economic hardship, and religious discrimination. The most egregious aspect of Jewish life in Russia during the early 1900s were the pogroms—violent, organised attacks on Jewish communities during which Jewish homes and businesses were looted and destroyed and Jews were physically harmed or killed. They faced discrimination in employment, education, residence, and religious freedom. Thus, when an opportunity for Louis to travel to America presented itself, the decision was easy. His father, Dimitri, was able to secure a passport and visa for his son; the ultimate plan was for the rest of the family to join Louis in America as soon as possible, Anti-Semitism in Russia untenable.

The journey from Russia to America was arduous, a trip marked by several stages and a multitude of challenges. The prospect of twelve-year-old Louis traveling alone bordered on the unimaginable, yet with one hundred rubles, half of the family’s fortune in his pocket, and his few possessions in a rucksack on his shoulder, Louis said his goodbyes not knowing if he would ever see his parents and sister again. He traveled alone from Moscow by foot, horse-drawn carriage, and rail stowed away in a freight car to the port city of Odessa. There, he purchased a steerage ticket, the lowest class of accommodations on the steamship Potemkin, and crossed the Black Sea to Constantinople, the capital city of the Ottoman Empire. On board he befriended Alexi Borlov, a teenager from St. Petersburg. The two boys were inseparable and traveled together; it was safer than being alone.

When the Potemkin docked in Constantinople, news of the tragic sinking of the Titanic spread rapidly throughout the city. The Titanic, thought to be unsinkable due to its advanced safety features, including watertight compartments and a double bottom, was operated by the White Star Line and was intended to be one of the most luxurious and advanced ships of its time. The Titanic set sail from Southampton, England, on April 10, 1912, headed for New York City, but tragically struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean, 370 miles off the coast of Newfoundland on the night of April 14. Despite efforts to evacuate passengers and crew, over fifteen hundred people lost their lives in one of the deadliest maritime disasters in history.

Louis and Alexi were shaken to the core by the news; however, despite their hesitation and trepidation, they boarded the Archimedes, a Greek-registered vessel, and set sail for Barcelona. The four-day trip across the Mediterranean Sea was beautiful and uneventful. The teenagers spent a week in Spain, slept in flophouses for a few pesetas a night, begged for scraps of fish and chicken at street kitchens and markets, and marvelled at the Gaudi architecture on display in the city.

Their twelve-day transatlantic crossing from Barcelona to New York was booked on the RMS Mauretania, a British ocean liner operated by the Cunard Line. The ship was one of the fastest and most luxurious of its time; however, the two Russian expatriates would not experience such elegance as steerage passengers. Instead, they were housed in the lower decks in large dormitory-style rooms with bunk beds and unsanitary toilets and sinks and ate their meals in a mess hall. Because they were young, Russian, Jewish, and traveled alone, they were often the target of taunts and ridicule from other passengers. There was one bright ray of hope: neither Louis nor Alexi was seasick, nor did they become ill with cholera and typhus, maladies that plagued many of their fellow passengers. The sight of the Statue of Liberty in New York emboldened their spirit; together they endured a long, difficult journey under horrendous conditions in hopes of finding a better life in America.

Upon arrival at Ellis Island, Louis and Alexi, as well as all other immigrant passengers, experienced immigration inspection and customs processing that involved a cursory medical examination, document checks, and interviews conducted by United States immigration officials. The government agents were unable to pronounce Louis’s surname, Rothoweskevitz, and shortened it to Roth, which they stamped his papers. “Welcome to America.”

Lou Roth and Alexi Borlov were determined to find and live the American dream. It was a Sunday afternoon when they exited the cavernous immigration hall and were swept up in a fast-moving mob of humanity—men, women, and children carrying their meagre belongings in frayed luggage and boxes to the dock. With the Statue of Liberty dominating the skyline of the of New York Harbor, they boarded the ferry for the short ride from Ellis Island to Battery Park. Together they disembarked from the ferry and were greeted by the sight of lush greenery, meticulously manicured lawns, and winding pathways. The park at the southernmost point of Manhattan was an oasis bordered by the harbour on one side and rising skyscrapers on the other. Families picnicked on the grassy lawns, children chased each other around the playgrounds, and couples strolled hand in hand along the waterfront promenade. As the sun set over New Jersey to the west, the kinetic energy of the city began to fade, replaced by the tranquility of lapping waves against the shore. Battery Park was a place of serenity and sanctuary. The weary travellers were overjoyed. The sound of freedom was pervasive.

Louis and Alexi went their separate ways. Alexi had family in Buffalo, New York, and departed for the railroad station to board a train for the final part of his journey. Together they accomplished an unimaginable feat: a five-thousand-mile trip from Russia to America in pursuit of freedom and opportunity. Louis embraced his companion and said, “Do svidaniya. Puteshestvuy bezopasno, moy drug. Nadeyusz uvidet tebya snova. (“Goodbye. Travel safely, my friend. I hope to see you again.”)2

Michael and Holly hope you enjoyed this extract from his book, Both Sides of the Same Coin.

Did the themes of hope and pursuing the early-twentieth-century ‘American Dream’ resonate? Do you have family stories of transatlantic migration? Join us in the comments as we discuss our thoughts on this piece.

What to write for the Society of History Writers?

All the details you need to know can be found in the post below. I look forward to hearing from you soon.

If you enjoyed this extract, here are three book excerpts we published in 2024.

Want to find out more about the Society of History Writers?

https://www.bothsidesofthesamecoin.com/about-the-book/

Author Michael Weiner speaks Russian fluently and has edited accordingly. He asks, however, more importantly whether Lou and Alexi would have spoken Yiddish instead of Russian with each other?

Fascinating Holly, I love the history you’ve presented so well in this piece. Thank you!

My grandfather was a German Russian from Crimea. leaving the rumors of future German pogoms. He stowed away on a ship leaving for America, and settled in Krem, North Dakota (named after Crimea) a community of Crimean and Ukrainian immigrants, which during that time period was all called Russia.