Propaganda Girls: The Secret War of the Women in the OSS

A guest article by Lisa Rogak | March 2025

The stakes were high: they knew that not every “believable lie” they made up worked out, and there was the hard truth that people died as a result of their brainstorms. “I tried to push it out of my head,” said Betty.

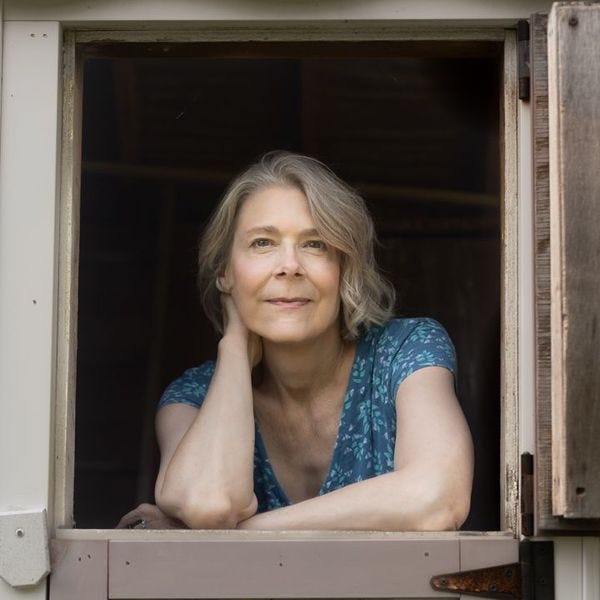

About Lisa Rogak, this week’s guest writer

Lisa Rogak is a New York Times bestselling author with multiple publications to her name, including Haunted Heart: The Life and Times of Stephen King, Michelle Obama In Her Own Words, and A Boy Named Shel: The Life and Times of Shel Silverstein.

To celebrate the launch of her latest book, Propaganda Girls: The Secret War of the Women in the OSS (available March 2025), Lisa has kindly shared an extract with members of the Society of History Writers.

“An astonishing slice of untold WWII history, Propaganda Girls is a stunning feat of storytelling. Rogak’s riveting narrative grants the often unknown but courageous women behind the OSS their much-deserved moment in the spotlight.”

Ric Prado, bestselling author of Black Ops: The Life of a CIA Shadow Warrior1

If you’re new here, the Society of History Writers is founded upon the principle of collaboration. It’s the ONLY space on Substack dedicated to bringing writers of history and historical fiction together to share their experience, grow in their craft, and share their writing exclusively with a growing worldwide audience. I am honoured to provide this space to spotlight your writing and share it with colleagues and readers across the world.

Propaganda Girls: The Secret War of the Women in the OSS

Lisa Rogak

During the last brutal eighteen months of World War II, American troops in the European and Far East theaters began to notice a significant uptick in the number of Axis soldiers and collaborators who were surrendering—peacefully and willingly—to the Allies.

Defeated German and Japanese troops stumbled across enemy lines in Europe and Asia with one hand thrust in the air, waving a piece of paper with the other. In some cases, it was a tattered scrap of fabric fashioned into the globally recognized white flag of surrender.

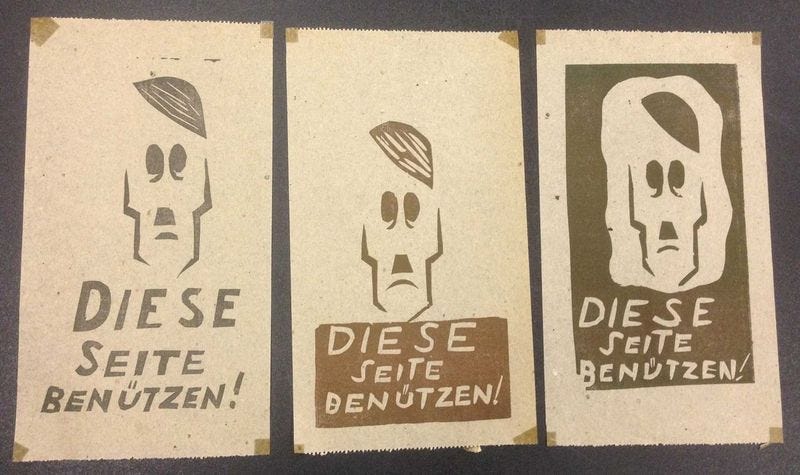

But many of the war-weary soldiers brandished leaflets, newspapers, and letters that had served as their personal breaking points, convincing them that theirs was a war that was no longer worth fighting for. One half-starved German even handed over a couple sheets of rough toilet paper with Hitler’s face printed on it as his ticket out of the war.

The Allied welcoming committee patted down the enemy soldiers before sending them on to intelligence officers, followed by the first good meal they’d had in months. They tossed the well-creased, sweat-stained papers in the burn pile along with their enemies’ threadbare uniforms.

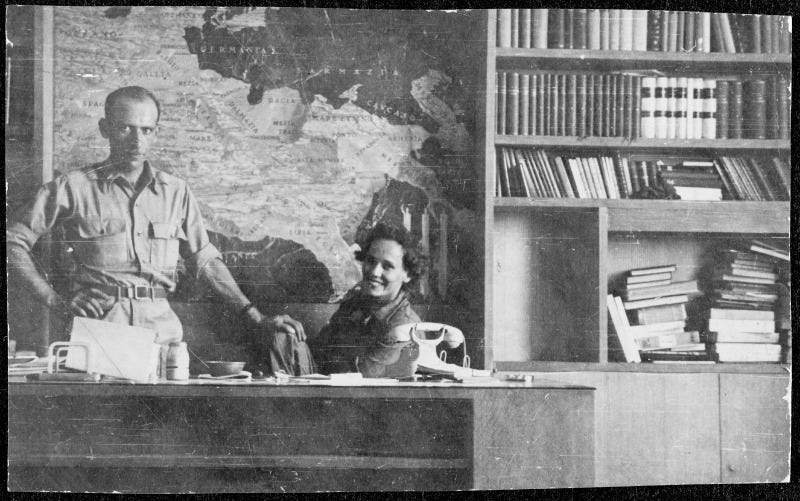

Neither the Allied nor Axis soldiers realized it, but many of the broadsides, pamphlets, and other documents the defectors presented in surrender came from a common source. What’s more, they were totally fake, a secret brand of propaganda produced by a small group of women who spent the last years of the war conjuring up lies, stories, and rumors with the sole aim to break the morale of Axis soldiers. These women worked in the European theater, across enemy lines in occupied China, and in Washington, DC, and together and separately, they forged letters and “official” military orders, wrote and produced entire newspapers, scripted radio broadcasts and songs, and even developed rumors for undercover spies and double agents to spread to the enemy.

Outside of a small group of spies, no one knew they existed.

* * *

The four women of Propaganda Girls— Elizabeth “Betty” MacDonald, Jane Smith-Hutton, Barbara “Zuzka” Lauwers, and celebrated German-American actress Marlene Dietrich—worked for General “Wild Bill” Donovan’s Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, the precursor of today’s CIA. Their department, the Morale Operations branch— or MO—was in charge of producing “black propaganda,” defined as any leaflet, poster, radio broadcast, or other public or private media that appeared to come from within the enemy country, either from a resistance movement or from disgruntled soldiers and civilians. In essence, black propaganda was a series of believable lies designed to cause the enemy soldiers to lose heart and ultimately surrender, but it was also aimed at occupied populations and soldiers captured for cheap labor, to encourage them to rise up against their oppressors and join the winning side.

Donovan, who had studied Nazi black propaganda, knew how effective these tactics could be. “Subtly planned rumor and propaganda [can] subvert people from allegiance to their own country,” he said. “It is essentially a weapon of exploitation, and if successful can be more effective than a shooting war.” While officers in other departments refused to hire women, Donovan specifically searched them out when he began to staff his new MO branch, as he believed they would excel at creating subversive materials.

“General Donovan believed that we could do things that the men couldn’t,” Betty said years later. “We were able to think of a lot of gossipy things to do for MO that men never would have thought of. I don’t want to brag, but women can hurt people better, maybe, than men could think of. Women seemed to have a feeling for how to really fool people.”

* * *

Donovan liked quirky people, and Betty, Zuzka, Jane, and Marlene definitely fit the bill. All had careers that were highly unusual for women in the 1930s and ’40s, and they all yearned to escape the gender restrictions of the day that dictated they be mothers and wives, or teachers or nurses if they absolutely had to work. They all wanted more than their present lives provided, though they never lost sight of the fact that their efforts would have just one aim: to help win the war and bring American soldiers back home.

Their motivations for joining the OSS differed—two wanted vengeance, two craved adventure—and one served stateside while three headed overseas. But the one thing they shared in common was that all four were determined to serve their country in the best way they could: by using their brains.

Every office and project in every theater was woefully understaffed, so the women quickly learned to multitask everything while happily taking advantage of the utter lack of supervision to call their own shots. While the women often turned to spies and agents for intel to help them craft their writings, they occasionally had to do the dirty work themselves.

And because the work was so clandestine, when it came to paying contract workers and locals for their assignments, a little bit of creativity was in order: Betty became well practiced at slicing off the exact amount of opium to compensate a Burmese spy, while Zuzka paid a group of German POWs with an afternoon at a local Italian brothel.

The four women loved their jobs along with the autonomy they brought, while at the same time faced a boatload of challenges regardless of where they were serving. The women had to constantly fight for promotions and recognition, as well as deal with rampant sexism. Often, after her workday was done, Betty was called upon to serve coffee and sandwiches to her male coworkers, while Zuzka played cocktail waitress, serving drinks to male officers who she had brainstormed alongside just minutes before. But they took it in stride. As Zuzka put it, “Scheuklappen, we were always reminded, German for blinders,” she said. “Just look straight ahead at what you’re doing, and don’t worry about what the other guys are doing.”

The stakes were high: they knew that not every “believable lie” they made up worked out, and there was the hard truth that people died as a result of their brainstorms. “I tried to push it out of my head,” said Betty.

The women also faced constant danger, and their own lives were often at risk: Betty worked in India and behind enemy lines in China, where a sizeable contingent of locals didn’t want the Americans interfering in their affairs. Zuzka regularly interrogated German POWs who could snuff out her life with one well-aimed finger to the throat. And Hitler had placed a bounty on Marlene’s capture from the moment she became a US citizen.

But if one more leaflet, radio broadcast, or well-turned phrase would cause just one German soldier to feel that maybe Hitler wasn’t worth fighting for any longer, well then it was worth the twelve-hour days, giant bugs, lousy food, and living in tents thousands of miles from home.

The women were extremely productive over the roughly eighteen months they worked for the OSS, cranking out hundreds of articles, letters, leaflets, and radio scripts. They even intercepted postcards and letters from enemy soldiers, erasing any positive messages and instead adding news of starvation and lost battles to dishearten family back home. The women had to take particular care to make sure each piece would “pass,” that civilians and troops would believe it came from a resister or disgruntled soldier from within their own country. If there were any doubts, Allied soldiers could be at risk.

* * *

When the women who would become known as Donovan’s Dreamers first came on board, Donovan gave them some plum advice, words that none of the women had heard before:

“If you think it will work, go ahead.”

For these unconventional women, planting victory gardens, wrapping bandages, and buying war bonds wasn’t going to cut it. Wild Bill was happy to help. He needed highly intelligent and creative women who could think on their feet, were fluent in at least one foreign language, and could hit the ground running.

In Betty MacDonald (later McIntosh), Barbara “Zuzka” Lauwers, Jane Smith-Hutton, and Marlene Dietrich, he had found four of the best.

Thank you Lisa Rogak for sharing this extract from your latest book, Propaganda Girls!

Make sure to let Lisa know what you thought in the comments, and share this post with anyone you think would enjoy reading Propaganda Girls.

If you enjoyed this extract, here are three recent guest posts featured on the Society of History Writers.

Want to find out more about the Society of History Writers?

Quotation from: https://www.lisarogak.com/

Wow, that's amazing. My great aunt was an early OSS agent, I wonder if she is in the book! That would be really cool!

I can’t wait to read the book!