Rebellion and Faith: Caste War of Yucatán, the Church of the Speaking Cross and the Cruzob Maya

Jeanine Kitchel | July 2025

Dear History Writers,

It is a delight to bring you this week’s guest article, by long-time friend of the Society

. With multiple guest posts already published (which you can find linked at the end of this post), Jeanine has opened up the world of the Maya to us, bringing its culture to life through the stories they told and the material culture they left behind. This week she touches on one of the more challenging parts of Maya history - the Caste War.All the best as always,

Holly

Editor, the Society of History Writers

Hello there! I’m currently studying for a PhD in Archaeology at Oxford, researching the role of women in the social and political developments of 6th- and 7th-century England and France. With a worldwide readership of over 1,500 (plus over 4,400 on my primary newsletter Medieval Musings), I provide a platform for the words of history writers at every stage of their career. Opportunities to contribute open up regularly, so make sure you’re subscribed to hear before anyone else! Our top 3 posts of all time have been an interview exploring the non-existence of medieval feminism, a guest post connecting the tyranny and injustice of Iron Age warrior queen Boudicca to the present day, and a hilarious journey through the myth of Arachne. You can support my work by becoming a paid subscriber at the link below or by making a one-off donation HERE. Thanks!

Jeanine Kitchel

Jeanine Kitchel writes about Mexico, the Maya and the Yucatán. Her ongoing love of Mexico led her to the Yucatán where she built a house and opened a bookstore in Puerto Morelos. Author of four books, Jeanine’s work has appeared in The Miami Herald, The News, Mexico City, Herald International, Mexico City, Fodor's Travel Guides, Mexico File, MexConnect, Sac-Be and more. Find her on Substack at the link below.

Rebellion and Faith: Caste War of Yucatán, the Church of the Speaking Cross and the Cruzob Maya

Jeanine Kitchel

Hola, Amigos! I first read about the Caste War in Michel Peissel’s adventure tale, The Lost World of Quintana Roo. In 1963, it was still a Mexico territory and would not achieve statehood until 1974. Yes, it was unruly and sparsely populated with dense mangroves and jungle, but of even greater importance to Peissel was that the Caste War had ended with a half-hearted truce only decades prior to his walk-about. Tempers still flared, and the only requirement granting easy passage was that one must be a person of color, which Peissel was not. How did we get here? To an all out war? Allow me to tell you an amazing story that ends with a speaking cross.

Living in the land of the Maya one takes for granted the solemn undercurrent of a revered, majestic culture that built pyramids, developed the concept of zero, and for centuries, quietly held their ground against the Spanish when their Aztec neighbors had succumbed in a heartbeat.

While sunbathing on endless white sand beaches, snorkeling off the Great Meso-America Reef or simply kicking back to enjoy Mexico’s gracious hospitality, it’s easy to forget to whom one owes allegiance in Quintana Roo. But just beneath the surface of a postcard perfect existence lies a Yucatán tale that isn’t much talked about but has set the tone for the past century: the Caste War of Yucatán.

When cultures collide, history requires a winner and a loser. But in Quintana Roo after the Caste War, which began in 1847 and ended first in 1901 and again in 1935 with a half-hearted truce, it’s difficult to determine who won the battle and which side lost the war.

Unsafe Passage

From 1847 until the 1930s, the Caste War made it impossible for a light-skinned person to walk into the eastern Yucatán or the territory of Quintana Roo and come out alive. This was a place where only indigenous Maya could safely roam. Anyone with light skin was killed on sight. What caused the fierceness of this Maya uprising that lasted nearly a century?

No single element alone instigated the rebellion, but as in most revolutions, a long dominated underclass was finally pushed to its limits by an overbearing ruling class that had performed intolerable deeds. Indentured servitude, land grabbing, and restrictive water rights were but a few issues that pushed the Maya into full-fledged revolt against their Yucatan overlords.

Mexican war and the Maya

The history of the Caste War, not unlike Mexico’s dramatic history, is complicated. Mexico’s successful break with Spain led to changes in the Yucatán government, including arming the Maya to help fight the Mexican war against the US in Texas.1 Maya numbers were needed to assure victory. Armed with rifles and machetes, this tactic backfired in Valladolid, considered the most elitist and race conscious city in the Yucatán.

After a decade of skirmishes, in 1847, when the newly armed Maya heard one of their leaders had been put to death by firing squad, a long simmering rebellion broke out into full-fledged battle. The Maya rose up and marched on Valladolid, hacking 85 to death by machete, burning, raping, and pillaging along the way.

Valladolid massacre

Merida braced itself, sure to be the next staging ground for what was fast becoming a race war. In retaliation for the Valladolid massacre, Yucatecans descended on the ranch of a Maya leader and raped a 12-year old indigenous girl.

With this affront, eight Maya tribes joined forces and drove the entire white population of Yucatán to Merida, burning houses and pillaging as they went. So fierce was the slaughter that anyone who was not of Maya descent prepared to evacuate Merida and the peninsula by boat.

But just as the Maya tribes approached Merida, sure of victory, fate intervened when great clouds of winged ants appeared in the sky. With this first sign of rain coming, the Maya knew it was time to begin planting. They laid down their machetes against the pleadings of their chiefs and headed home to their milpas (cornfields). It was time to plant corn—a thing as simple and ancient as that.

Yucatecans stage a comeback

In 1848 the Yucatecans staged a comeback, killed Maya leaders, and reunified. But as the Maya harvested corn planted in hidden fields, they kept fighting, relying on guerrilla tactics to preserve the only life they knew.

Throughout it all, the Maya were pushed to the eastern and southern regions of the Yucatán Peninsula and Quintana Roo, as far south as Bacalar. Mexico slowly gained control over the Yucatán, but rebel Maya held firmly onto QRoo, using Chan Santa Cruz (Felipe Carrillo Puerto) as their base.

Church of the Speaking Cross

Tired from years of struggle, the Maya regained confidence from an unlikely source: a talking cross found deep in the jungle near a cenote. Revolutionary Jose Maria Barrera, driven from his Yucatán pueblo, led his band of people to an uninhabited forest and to a small cenote called Lom Ha (Cleft Spring). There he discovered a cross that was carved into a tree. The cross bore a resemblance to the Maya tree of life, La Ceiba, and a new religion formed around it, the Cult of the Speaking Cross, centered in the Tulum area.

Barrera, a mestizo, said the cross transmitted a message which was later given as a sermon by Juan de la Cruz (of the Cross), a man trained to lead religious services in the absence of a Mayan priest. Barrera also used a ventriloquist, Manuel Nahuat, as the mouthpiece of the cross, and through this medium directed the Maya in their war effort, urging them to take up arms against the Mexican government, assuring the people of the cross they would attain victory.

From this speaking cross a community evolved—Chan Santa Cruz (Little Holy Cross)—and its inhabitants came to be called Cruzob, or followers of the cross. By chance, the cross bore three elements sacred to the Maya: the Ceiba tree, the cenote, and a cave. The cross was found growing on the roots of a Ceiba, the Maya tree of life, which sprung from a cave (caves were sacred spots to the Maya), by a cenote, which the Maya believed was the place where the rain gods lived, making it easy for the Maya to accept this supernatural phenomenon.

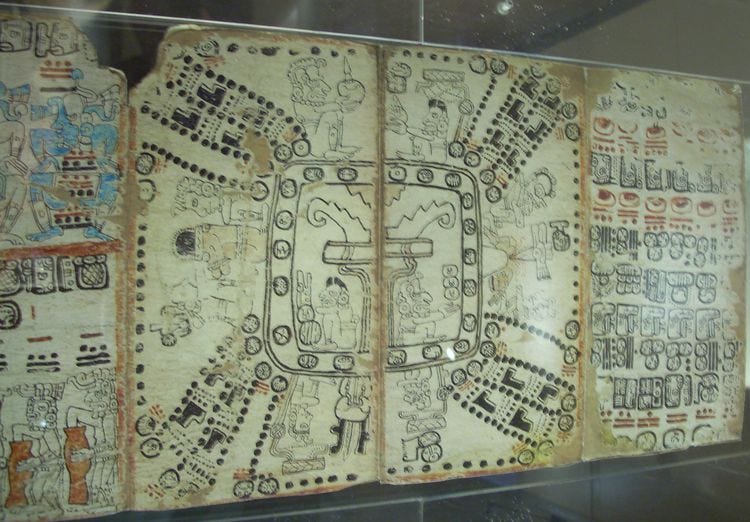

It was also not a stretch for the Maya to believe the cross spoke to them. In the Chilam Balam, an ancient Maya text, priests were described as hearing voices from the gods. So, even this aspect of mysticism fell into an acceptable myth.

To the Chan Santa Cruz, the voice of God came from that cross in that tree. The the cross was inspired by a shamanic ventriloquist—the man speaking to them through the cross was God’s chattel, a mouthpiece of the gods. A shaman. The Cruzob believed this tree and this cross were connected underground, 100 kilometers from Lom Ha cenote to Xocen—the center of the world—from where the first speaking cross originated.

As scholar Nelson Reed wrote in The Caste War of Yucatán, during times of extreme cultural stress, that’s when prophets arise. In 1850 the Maya were losing the war and their religious structure was falling apart—their priests and saints had been expelled with all Spanish heritage during the war.

Four crosses are said to exist at counter points—tips of the cross—marking the boundaries more or less of the Cruzob Maya. The religion is still practiced in these four sacred shrine villages— X-Cacal Guardia, Chancah Veracruz, Chumpon and Tulum—whose geographic positions roughly describe the territory of the Cruzob Maya.

In 1935, the Chan Santa Cruz from these last holdout villages signed a treaty of sorts which allowed the rest of Mexico to rule them. The jungle-wise Maya had kept the Mexican government at bay for over 50 years.

Counterpoint in Tulum

I visited the church of the speaking cross in Tulum years ago. Hiding in plain sight and sitting very near el Centro, it was a humble white-washed structure surrounded by trees. A narrow path with overgrown shrubs on either side disguised the entrance that led up to it. Before entering the churchyard, I passed through an enclosed area watched over by a custodial guard. He gave a nod and I continued on towards the church. A posted sign instructed that shoes and hats were forbidden, as were photos.

Inside votive candles were lit and the musky scent of copal wafted through the darkened church. The interior was a large open room with seating. Straight ahead, three crosses covered in small white huipil-like veils sat on an otherwise barren altar. The room held little else except for a Maya woman kneeling on a blanket in a rear corner. I stepped back outside into blinding Yucatán sunshine.

Original Cross

Of the four crosses held at the counter points, one is said to be the original. Tixcacal Guardia village elders fiercely guard what they swear is the original speaking cross and let no outsiders near it. It's kept in a city within a city, much like the Vatican, according to blogger Logan Hawkes, safely hidden away from all save the Cruzob spiritual leaders—a head shaman and a circle of elders.

For generations, Maya have flocked to these outposts to worship a wooden cross that became a dynamic part of their history during the Caste War of Yucatán. In Tixcacal Guardia, the church which houses the cross is open to the public on feast days only, but even then it's said the artifact is not on display. It's located on an altar covered with veils in a blocked-off section called La Gloria. No one is allowed to enter the inner sanctum and the cross is guarded day and night by Maya from the region.2

Even though Chan Santa Cruz, the rebels' capital city, now Felipe Carrillo Puerto in southern Quintana Roo, is not one of the counter points of the cross bearers, it was the main stronghold of the Cruzob Maya rebels during the war. To this day a rotating team of followers keep one week vigils at a local chapel where a flower-adorned shrine is set up in honor of the cross. Tihosuco, an hour to the northwest, is home to the Caste War Museum.

With history this unique, it's not hard to realize that the newly founded Riviera Maya is but a shell for a more mysterious land of an ancient, respected people who have had an ongoing conversation with the gods and the universe for more than a millennium.

More information can be found in Nelson Reed’s excellent The Caste War of Yucatán and fall into the beauty of MacDuff Everton’s black and white photos in The Modern Maya, A Culture in Transition.

Thank you Jeanine for sharing this informative essay with us!

Do join me in expressing your thanks to Jeanine in the comments section, as well as asking her any questions you may have for her.

If you enjoyed this essay, then you might also enjoy Jeanine’s other contributions to the Society of History Writers, linked below.

Thank you for reading this post by the Society of History Writers! You can support my work by becoming a paid subscriber at the link below or by making a one-off donation HERE. Thanks!

Nelson Reed. The Caste War of Yucatán. Stanford University Press/Revised. 2002.

Macduff Everton. The Modern Maya, A Culture in Transition. University of New Mexico Press. 1991.

The Caste War is a fascinating and under-explored corner of history. I read Nelson Reed's book 30 years ago and happily re-read it recently. Thank you for surfacing this complex conflict again in this excellent post!